Disclaimer: This is a re-edited version of the original article posted on MyDramaList.com on the 5th of May, 2019. This version includes corrected linguistic errors, updated links, changed pictures, and a new passage on Godzilla: King of the Monsters (2019).

[Note:

For clarity’s sake, I mostly use the English transliterated form

Godzilla throughout this article, but I also refer to original Gojira

when the context requires it.]Gojira [ゴジラ], also known as the Big G, the God of Destruction, and the King of the Monsters, is a radioactive creature of biblical proportions who stomped his way into the Japanese cinema and became a worldwide pop-cultural icon. Many viewers love him, but also many regard him as campy. However, undeniable is the fact that, over the course of 65 years, there have been 32 feature films (including 3 Hollywood productions), an animated trilogy, two cartoon shows, and countless novels, comic books as well as video games. Godzilla is nowadays both a kaiju superstar in his own right and a profitable commodity for his owner, the Toho Studios. My attempt is to outline the history behind the cinematic monster and his impressively rich legacy.

My first introduction to Godzilla was back in 1998. Don’t worry, it was not like the Emmerich version became the first Godzilla flick I have ever seen. There was a lot of marketing buzz about this Hollywood blockbuster, but I was completely uninterested in it. All of a sudden, a Polish movie magazine fell into my 6-year-old hands which contained even more hype urging readers to see the American remake. However, there was also an article which provided an overview of the original 22 movies from the Showa and the Heisei series in form of chronologically organized titles with brief descriptions, posters, and monsters. That text became my guide list to Godzilla movies in the pre-internet era. After reading it, I was determined to see every single film listed there and I eventually fulfilled my resolution. The very first Godzilla movie I had the pleasure to see was Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah and to date, it remains my all-time favourite. So, without further delay, let’s get into the nitty-gritty of Japan’s favourite monster.

Character Overview

- Age: Unknown

- Height: 50 to 118 meters/164 to 387 feet (depending on a movie)

- Special powers: Atomic heat beam, extreme resistance to firepower

- Species: Prehistoric amphibious reptile (Predecessor: Godzillasaurus)

- Offspring: Minilla (Showa), Godzilla Junior (Heisei)

Origins

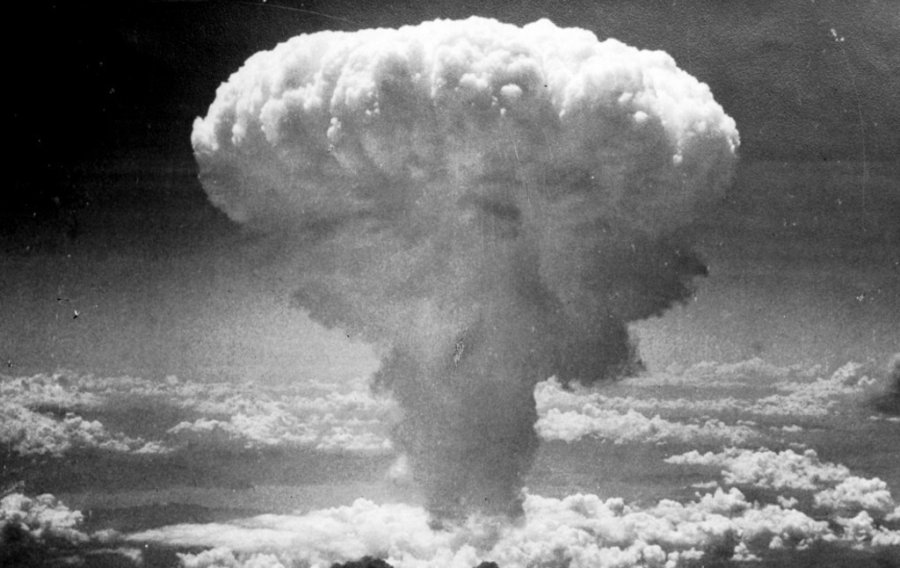

Contrary

to many misconceptions, Godzilla had a very meaningful beginning. He

started off as an allegory of nuclear holocaust and World War II trauma.

Japan was brought onto its knees after the bombing of Hiroshima and

Nagasaki in 1945. Then, the American occupation ensued which lasted up

until 1952. Throughout this period, Japanese filmmakers were forbidden

from acknowledging in any way the war and its atrocities. Nevertheless,

the public controversy was ignited in 1954 when, as a result of a

hydrogen bomb test performed at Bikini Atoll, 23 Japanese fishermen of

Daigo Fukuryu Maru tuna fishing boat were exposed to radioactive ash.

The event reminded Japan that the atomic weapon was still a tangible

threat, but it also inspired producer Tomoyuki Tanaka to make a movie

about a monster emerging from the sea depths as a side effect of nuclear

testing.

However, the nuclear test was not the only influence. With

the 1952 re-release of King Kong (1933) and the 1953 premiere of The

Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, Tanaka saw the potential for a monster film

made in Japan. Having obtained a green light from Toho, he brought on

board director Ishiro Honda, former Akira Kurosawa’s collaborator, and

Eiji Tsuburaya, the mastermind of Japanese special effects. The three

created the story and its destructive creature: Gojira, a combination of

words gorira [ゴリラ, gorilla] and kujira [クジラ, whale] serving to indicate

the monster’s power and might. His appearance was devised by art

director Akira Watanabe who blended attributes of various dinosaurs and

combined them with scaly, charcoal skin, anthropomorphic torso, dorsal

fins on the back, and a long tail. Godzilla’s famous roar, in turn, was

invented by legendary Akira Ifukube (the official composer of 11

Godzilla movies) who rubbed the strings of the double bass with a coarse

leather glove and played the recording back at a reduced speed. Talk

about ingenuity in the 1950s!

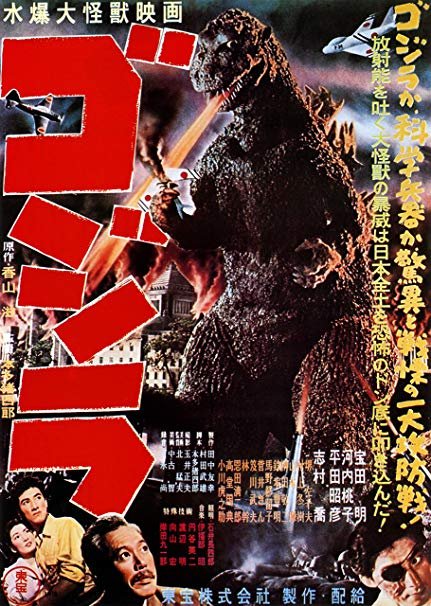

The First Movie

The original Gojira

movie hit the screens on November 3, 1954. It was the most expensive

Japanese production at that time (even surpassing the oversized budget

of Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai from the same year) and it became an instant

box office success. It has to be noted, however, that the first film

did not establish the conventional formula of spectacular monster

fights, army counterattacks, and invasions from outer space. The

original movie provides a very bleak and harrowing cinematic experience.

Images of utter destruction: Tokyo in flames, people suffering from

radiation, and dead bodies made the Japanese recall their wartime

trauma. Perhaps the most gutting image in the whole picture is that of a

crying mother who, while clutching her children in the midst of

explosions, says that they will soon join their father.

What is more

interesting, Godzilla is presented neither as an enemy nor as a symbol

of hate. As the story progresses, human characters perceive him as a

force of destiny, a metaphorical incarnation of Japanese arrogance who

takes revenge on civilization. In accordance with Ishiro Honda’s vision,

Godzilla was to behave like a living nuclear bomb, radiating as well as

torching everything and everyone on his way. As Tomoyuki Tanaka stated:

“Mankind had created the Bomb, and now nature was going to take revenge

on mankind” (source).

Surprisingly, the American audiences were not able to see the full, uncut version of the movie until 2004. Gojira was re-released in 1956 under the title Godzilla, King of the Monsters! (yes, the same name as the 2019 production). Most of the footage was reshot in order to incorporate journalist Steve Martin (played by Raymond Burr) as the lead character. While visibly weaker in comparison to the original, I find this version very watchable as well and it is worth checking out as a trivia.

Surprisingly, the American audiences were not able to see the full, uncut version of the movie until 2004. Gojira was re-released in 1956 under the title Godzilla, King of the Monsters! (yes, the same name as the 2019 production). Most of the footage was reshot in order to incorporate journalist Steve Martin (played by Raymond Burr) as the lead character. While visibly weaker in comparison to the original, I find this version very watchable as well and it is worth checking out as a trivia.

Special Effects

Of course, the

impact of Gojira would not be possible if it had not been for the

special effects department. Originally, Godzilla was supposed to be shot

using the stop motion approach as in the case of King Kong, but time

constraints (only two months to make the picture) forced Eiji Tsuburaya

to come up with the suitmation technique. It involves a man in a monster

suit placed within a carefully crafted miniature set and shot at an

appropriate frame rate (sometimes quicker or slower depending on the

shot). Many modern “critics” look upon this approach as outdated and

embarrassing, but they need to realize how ingenious and efficient it

was. Without it, we would not get 28 Godzilla movies.

Nevertheless,

if you think that suitmation was a piece of cake, then you could not be

more wrong. Haruo Nakajima, Kenpachiro Satsuma, and Tsutomu Kitagawa are

the most prominent actors who “played” Godzilla throughout the Showa,

Heisei, and Millennium series respectively and they all suffered through

a fair share of discomfort and pain. The suits were extremely heavy (up

to 100 kg/220 lb) and hot. The actors experienced such things as oxygen

deprivation, near-drowning, concussions, lacerations, and electric

shocks. In addition, each suit had to be made from scratch for a new

movie. As with regard to the sets, the miniatures had to be destroyed on

cue, which not always happened and resulted in the crew relentlessly

“rebuilding” the miniatures after hours.

Special effects changed and improved as time went by, but Tsuburaya’s technique remained largely unchanged. In fact, it was utilized on television in many Tokusatsu shows (Ultraman, Kamen Rider, Super Sentai). In the 1990s, the Heisei movies combined miniatures with cell compositing effects and digital graphics, whereas the Millennium era, in the 2000s, began blending CGI into the fights. Forgive me this subsection, but I felt I had to mention and give justice to people who made Godzilla seem real on film. Just check out their devotion even in recent years.

Special effects changed and improved as time went by, but Tsuburaya’s technique remained largely unchanged. In fact, it was utilized on television in many Tokusatsu shows (Ultraman, Kamen Rider, Super Sentai). In the 1990s, the Heisei movies combined miniatures with cell compositing effects and digital graphics, whereas the Millennium era, in the 2000s, began blending CGI into the fights. Forgive me this subsection, but I felt I had to mention and give justice to people who made Godzilla seem real on film. Just check out their devotion even in recent years.

Evidently,

Godzilla would be nothing without thespians whom he can trample on. A

variety of actors and actresses graced the screen alongside Godzilla

including such veterans as Akira Takarada, Momoko Kochi, Akihiko Hirata,

Takashi Shimura, Kumi Mizuno, Yoshio Tsuchiya, Koichi Ueda, Masato Ibu,

and Akira Nakao. All of them appeared in more than one movie, having

played various roles, but an absolute record-breaker is Megumi Odaka who

played the character of Miki Saegusa in six Godzilla movies. (Please,

Toho/Warner Bros. give her a guest role in new films already!)

The

success of the first movie immediately led to the production of a

sequel, Godzilla Raids Again, in which he was pitted against the first

antagonist, Anguirus. Though commercially successful, Toho did not pitch

another follow-up idea for seven years. The year 1962 saw the release

of King Kong vs. Godzilla which became an even greater success and set

the tone for the rest of the Showa Series. With the advent of colour

film, the style was no longer depressing, references to the war were

scrapped, and the socio-political commentary got replaced by a

light-hearted plot and monster battles. In the fourth movie, Godzilla

had to fight against another Toho star, Mothra; and by the fifth

picture, Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster, the Big G was presented as a

friendly anti-hero who had to defeat a new badass in town.

Godzilla’s

transformation into a positive superhero was laid out in three

subsequent productions: Invasion of the Astro-Monster, Ebirah, Horror of

the Deep, and Son of Godzilla. In spite of turning Godzilla into a

children’s hero, the films did manage to provide some social commentary.

For example, Godzilla vs. Hedorah raises the issue of Earth’s

pollution, whereas Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla expresses clearly

anti-American undertones. Yet, Godzilla also did such crazy stuff as

wrestling jumps, talking or even flying… In the mid-1970s, the economic

situation started to change in Japan. Godzilla was present on the silver

screen for 20 years already and the demand for new adventures simply

began trickling away. After 14 sequels, the series ended with Terror of

Mechagodzilla in 1975.

Heisei Series

Toho was very keen on

bringing back the King of the Monsters and they eventually achieved that

in 1984 with The Return of Godzilla (original title: Gojira (1984)).

The movie rebooted the franchise by ignoring all of the Showa films

apart from the original Gojira. The monster grew to 80 meters and became

more menacing in its appearance. Although The Return turned into a

welcomed success, Toho had no idea how to carry the story further. Thus,

they held a public contest and selected a script which became the basis

of Godzilla vs. Biollante. This installment turned into a fans’

favourite over the years, but it was not as successful as anticipated.

Toho’s

60th anniversary in 1992 provided the opportunity for another entry in

the series. Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah brought back the Big G’s

archenemy after two decades of absence. In addition, the movie gave us Godzilla’s background story as well as Mecha-King Ghidorah(!)

Consequently, King of the Monsters was pitted against good old foes in

Godzilla vs. Mothra and Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla II. Toho intended to

end the franchise at this point but delays with the announced American

version allowed them to produce two more pictures: Godzilla vs.

SpaceGodzilla (40th-anniversary film) and Godzilla vs. Destoroyah.

Personally, this is my favourite Godzilla series and I find it to be secretly genius. It has awesome monsters, great special effects, and brilliant music scores. The movies are closely knit together, showing a clear progression of Godzilla from a misunderstood monster to a ruthless destroyer to a loving father. Additionally, the ending of this series made me cry as much as I cried while watching The Lion King all over again (but ten times more heartbreaking!: *spoiler clip*).

Personally, this is my favourite Godzilla series and I find it to be secretly genius. It has awesome monsters, great special effects, and brilliant music scores. The movies are closely knit together, showing a clear progression of Godzilla from a misunderstood monster to a ruthless destroyer to a loving father. Additionally, the ending of this series made me cry as much as I cried while watching The Lion King all over again (but ten times more heartbreaking!: *spoiler clip*).

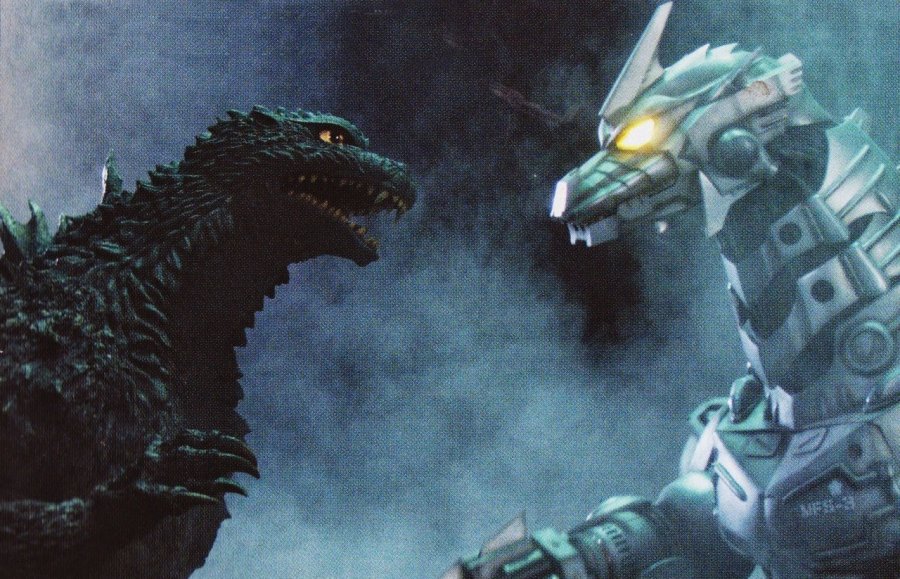

Millennium Series

After

the premiere of the abysmal Hollywood reimagining of Godzilla in 1998

(“That’s a lot of fish”), the fans raged across the globe and Toho

management gave the green light to a new film that was supposed to save

the King’s reputation. The result of this was Godzilla 2000: Millennium which,

similarly to The Return of Godzilla, ignored everything but the original

Gojira. The producers must have taken a liking to this approach because

almost every entry of the Millennium Series is a reboot happening in an

alternate timeline and ignoring everything that occurred earlier. The

notable exception is Godzilla X Mechagodzilla and Godzilla X Mothra X

Mechagodzilla: Tokyo S.O.S which constitute a two-part story that

references the Showa era. These two are definite highlights and my

favourite entries of this series. Though, many fans point to Godzilla,

Mothra and King Ghidorah: Giant Monsters All-Out Attack as the best

picture of this era. The 50th-anniversary film, Godzilla: Final Wars,

came out in 2004 to a mixed reception (I only liked parts of it).

Legendary Series (a.k.a. MonsterVerse)

Ten

long years have gone by since Godzilla’s retirement, but he gloriously

returned yet again in another Hollywood’s reinterpretation. Godzilla

(2014) directed by Gareth Edwards pays a lot more focus and respect to

the source material than the 1998 flick. The King is Japanese, its 1954

origins are referenced, and there are monster fights. I enjoyed every

minute of this film when I saw it on the big screen, so it is really

hard for me to comprehend all the bad rap this movie gets for not having

enough of Godzilla in it. This was a very good introduction into a

larger story that Legendary Entertainment is currently developing.

Speaking

of which, Godzilla: King of the Monsters (2019) won me over! It was a

breathtaking experience seeing this film in cinema. Indeed, it may have a

generic human drama and a couple of cheesy one-liners, but the action,

pathos, and the monsters are amazing! Hollywood is finally going down

the right path laid out by Toho decades ago. Godzilla vs. Kong (2021),

you’d better be good!

Shin Series

Following the enormous success

of Godzilla (2014), it became evident that Toho also wanted a piece of

the action. Being bound by the deal with Legendary, Toho cannot release a

Godzilla flick in the same year as Legendary’s prospective productions.

Hence, they gave director Hideaki Anno a very narrow time window

(summer 2016) to make a new movie. The result of this expensive and

hasty production is Shin Gojira (a.k.a. Godzilla Resurgence), a new take

on Godzilla’s monstrosity that ignores even the 1954 picture.

The movie became a huge hit at the Japanese box office and received wide critical acclaim. Godzilla’s unique appearance and powers might have been the main visual advantages, but the movie is unconventional in other ways as well. Steve Ryfle describes it in the following manner: “It’s not truly a monster or disaster movie at all, but a faux-documentary look at politicians and bureaucrats responding to a doomsday scenario, with all of the deadlocked meeting, endless discussion, conference calls and staring at computer screens […] What the film eschews in personal emotion, however, it replaces with a sense of national pride, embodied not by the bumbling, indecisive, pass-the-buck, old-school politicians […] but by younger, patriotic and clear-headed generation that leads the country out of the mess” (source). In other words, Shin Gojira turns into an ideological manifesto in the wake of post-Fukushima Japan. While I appreciated the risks the film took and a new direction of the story, it did not make a lasting impression on me. Call me an old-fashioned viewer, but I go with J-Taro Sugisaku’s claim that the primary reason behind Shin Gojira’s popularity was the presence of Satomi Ishihara as the female lead…

The movie became a huge hit at the Japanese box office and received wide critical acclaim. Godzilla’s unique appearance and powers might have been the main visual advantages, but the movie is unconventional in other ways as well. Steve Ryfle describes it in the following manner: “It’s not truly a monster or disaster movie at all, but a faux-documentary look at politicians and bureaucrats responding to a doomsday scenario, with all of the deadlocked meeting, endless discussion, conference calls and staring at computer screens […] What the film eschews in personal emotion, however, it replaces with a sense of national pride, embodied not by the bumbling, indecisive, pass-the-buck, old-school politicians […] but by younger, patriotic and clear-headed generation that leads the country out of the mess” (source). In other words, Shin Gojira turns into an ideological manifesto in the wake of post-Fukushima Japan. While I appreciated the risks the film took and a new direction of the story, it did not make a lasting impression on me. Call me an old-fashioned viewer, but I go with J-Taro Sugisaku’s claim that the primary reason behind Shin Gojira’s popularity was the presence of Satomi Ishihara as the female lead…

In

between 2017 and 2018, Toho released together with Polygon Pictures a

trilogy of animated Godzilla films: Godzilla: Planet of the Monsters,

Godzilla: City on the Edge of Battle, Godzilla: The Planet Eater.

Although the fandom generally disliked the trilogy for not including

monster fights, I think that the anime provides a very interesting

what-if scenario for Godzilla, grounding it deeper within the sci-fi

convention. In addition, this series gave us, arguably, the most hellish

reimagining of King Ghidorah since his first appearance in 1964.

Knock-offs and Imitations

As

with every other major phenomenon, Godzilla became the source of many

copycats. The most prominent of these is Gamera, Godzilla’s rival from

Daiei company, who appeared in 12 movies to date. Other

Godzilla-influenced monsters include Repticulus, Gorgo, Yonggary, and

Pulgasari. The last one is known more than anything else for the unusual

story behind its making. The glorious leader of the North Korean

nation, Kim Jong-Il was so desperate to produce a hit that he kidnapped a

South Korean actress and director, as well as tricked the Heisei

Godzilla crew, in order to create Pulgasari. For more information about

this crazy story, please refer here.

In Other Media

Apart from

the cinema, Godzilla also appeared on television. He was given his own

animated toy show called Godzilla Island (1997-1998) as well as a series

of animated shorts called Godzilland co-produced by an educational

company Gakken (children were supposed to learn writing and maths with

the King). In the late 1970s, Hanna-Barbera Productions made their own

Godzilla cartoon, whereas 20 years later Sony Pictures produced

Godzilla: The Series, a cartoon sequel to the 1998 movie. The King

received a string of video games as well (the most prominent one being

Godzilla: Destroy All Monsters Melee on Gamecube). Also, Godzilla did

manage to battle the Avengers (yes!) in a series of Marvel comics

between 1977 and 1979. Unfortunately, the only thing we are missing

today is a full-blown J-drama set in the aftermath of the Kaiju

apocalypse… (You can do this FujiTV!)

Selected Trivia

- In 1985, New World Pictures released the U.S. cut of The Return of Godzilla. Similarly to Godzilla, King of the Monsters! from 1956, Raymond Burr was included into the film, reprising the role of American journalist Steve Martin.

- The second best screenplay of 1986’s public contest involved Godzilla fighting against a supercomputer. It later served as the basis for a science-fiction production called Gunhed.

- After the release of Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah, Toho wanted an immediate follow-up titled Counterattack of Ghidorah, but they opted instead for Godzilla vs. Mothra because the latter monster was very popular among female fans.

- A 1992 Nike Ad featured Godzilla playing basketball against Charles Barkley.

- Japanese baseball star Hideki Matsui was nicknamed “Godzilla” for his achievements and he even made a cameo in Godzilla X Mechagodzilla.

- In 1992, one of the monster’s costumes (worth $39,000) was stolen from a Toho garage, only to be found washed up on the shore near Tokyo, where it unexpectedly terrified a lady who had gone out for a stroll.

- Patrick Stewart presented Godzilla with an MTV Lifetime Achievement Award in 1996.

- In Japanese, Godzilla is referred to with the gender-neutral pronoun “it”, while in English as “he”. In Polish, Godzilla’s gender form is “she” (sorry, our inflectional language is pretty messed up). Toho officially confirmed that the King’s gender is male.

- Since 2015, Godzilla has been peering down at bystanders from one of the buildings at Shinjuku (as presented by photo at the top of the section). He was also nominated by Shinjuku ward of Tokyo to be an official cultural ambassador.

Personal Movie Recommendations

- Gojira (1954): The movie that started it all. If you are not interested in the monster theme, it is still worth checking this film out for human drama and social commentary.

- Ghidorah, The Three-Headed Monster (1964): The first appearance of King Ghidorah and the combined fight between Godzilla, Mothra, and Rodan. Best to check out before the 2019 movie.

- Invasion of the Astro-Monster (1965): An exemplary instance of the Showa era's greatness. Godzilla duels King Ghidorah once again, but this time there is a lot of science-fiction stuff going on.

- Godzilla vs. Biollante (1989): The King's triumphant step into the 1990s where he fights a biologically engineered creature.

- Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah (1991): One of the best sequels out there. Evil time travelers, altering the past, an android, and two incarnations of King Ghidorah.

- Godzilla vs. SpaceGodzilla (1994): Considered by many as the weakest Godzilla film of all time, but it really grew on me over the years, so I give this story my recommendation. Spacegodzilla is awesome!

- Godzilla vs. Destoroyah (1995): The only movie in the whole franchise which provides some sense of closure. The main antagonist is truly terrifying.

- Godzilla X Mechagodzilla (2002): I recommend this mainly because of Kiryu who is the best incarnation of Mechagodzilla. Very good special effects and the fights.

- Godzilla X Mothra X Mechagodzilla: Tokyo S.O.S. (2003): A follow-up to the previous film. This time Mothra joins the party as well. I wish the filmmakers could carry on this story arc. There is a post-credits scene which went to a complete waste because it was not referenced anywhere later on.

Well,

I guess this is the end of my lengthy retrospective look at the King of

the Monsters and his extensive legacy. As of May 2018, Toho announced

that there will not be a follow-up to Shin Gojira. However, there are

plans for a shared cinematic universe between Godzilla and other Toho

monsters after 2021. Saddening is that fact that none of the original

crew members will be working on new movies anymore, because they either

passed away or retired. Nevertheless, this is the way our world works.

Times change, people move on, but Godzilla always stays the same,

regardless of whether or not he is a hero, destroyer, or a force of

nature. He will be with us for the next 65 years to come.

Make sure

to check out Easter eggs in the hyperlinks as well as my sources below.

Although I tried to contain as much as info as possible, this task

proved to be a fool’s errand: EW.com, Reuters.com,

JapanTimes.co.jp, BBC.co.uk, Salon.com, InTheseTimes.com, Motherboard.vice.com, Mangauk.com, SFcrowsnest.info, FactFiend.com, Metro.co.uk, GeeksandSundry.com,

Britannica.com, IGN.com, Inverse.com, MentalFloss.com,

TokyoCreative.com, HistoryVortex.org, ScifiJapan.com, ScreenRant.com,

TohoKingdom.com, Kenpachiro Satsuma Interview, Megumi Odaka Interview,

and Bringing Godzilla Down to Size (a documentary).

If you still

can’t get enough of reading about Godzilla, then I also recommend two

books: Japan’s Favourite Mon-Star: An Unauthorized Biography of the Big G

by Steve Ryfle and Millennial Monsters: Japanese Toys and the Global Imagination by Anne Allison.

I hope that you enjoyed the article as much as I did writing it. Have you seen any Godzilla movies? Would you like to check out some of the mentioned ones? Please write in the comments. Thank you for reading.

«Enjoyed this post? Never miss out on future posts by following us»

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comment moderation is switched on due to recent spam postings.